Meta, Google Face Barrage of Pixel Lawsuits in Digital Privacy War

META PLATFORMS INC. AND GOOGLE are currently facing nearly 70 lawsuits involving large companies and some hospital systems or individual health care providers utilizing Pixel tracking tools embedded on their websites and applications. Sensitive private data such as financial information gathered from filing tax returns online or patient healthcare information stored on patient portals is being actively tracked and sent to Meta and Google for both analytical and advertising purposes.

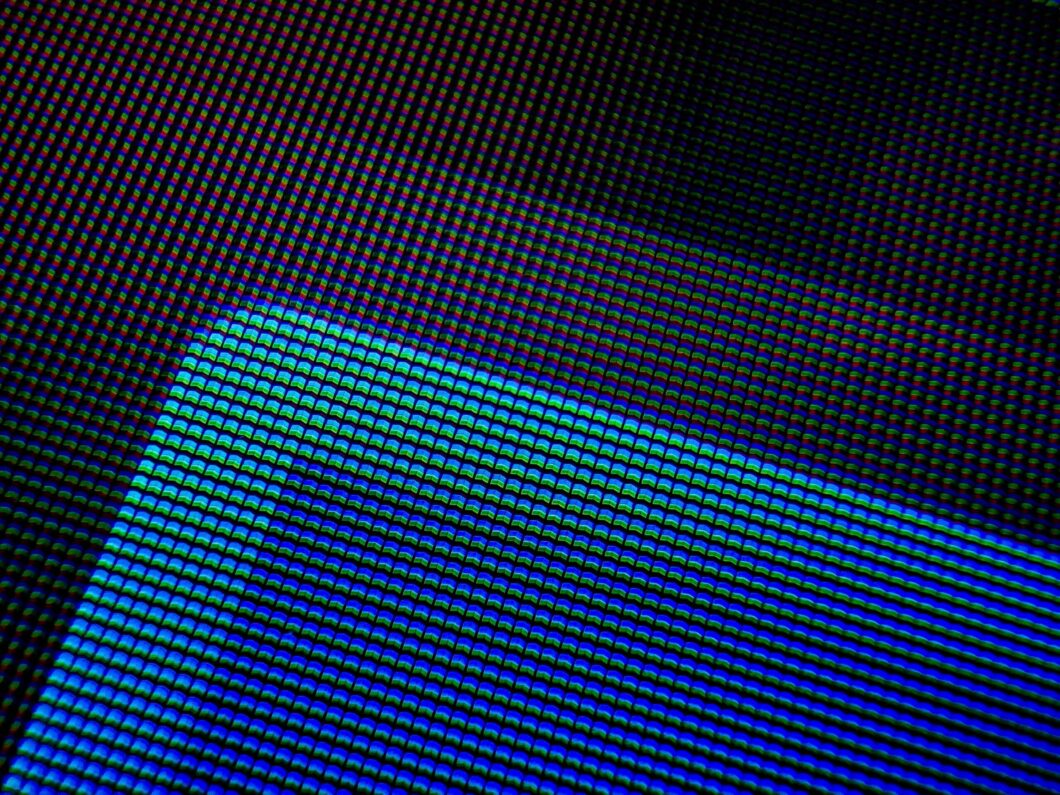

Tracking pixels are a 1×1 Pixel graphic that serves as a snippet of code used for tracking user behavior, site conversions, web traffic, and other metrics generated from a site’s server. In 2018, Meta told Congress that there were more than 2 million Pixels across the web, which at the time, was one of the largest data-harvesting operations most internet users had ever seen. Meta makes their Pixel code freely available to anyone and any business – thus the amount of Pixel tracking has exponentially grown since Meta testified before Congress. The analytical information that companies gleam from Pixel tracking is paying off and is featured on everything from fast food companies such as Chick-Fil-A, media companies like iHeart Radio, and even tax-filing websites such as Tax Slayer or TaxAct.

Pixel Tax Data

On November 22, 2022, theverge.com co-published a report with The Markup, revealing that Pixel tracking tools located on several renown American tax-filing websites were sending individual tax filers’ contact and financial information to Meta and Google. From January to July 2022, The Markup tracked websites’ use of the Pixel as part of the Pixel Hunt in partnership with Mozilla Rally. Participants of the Pixel Hunt installed a browser extension that provided The Markup with a copy of all data shared with Meta through the Pixel. H&R Block, Tax Slayer, and Tax Act utilized Pixels on their websites and applications that sent financial data to Meta according to the data-driven report.

TaxAct’s Pixel sent some of their users’ tax data to Facebook, including their filing status, adjusted gross income, and the amount of their tax return, if applicable. TaxAct says it has about “three million consumer and professional users”. The Pixel Hunt also revealed that TaxAct’s embedded Pixels were sending data to Google Analytics as well. The Pixel Hunt also revealed that Tax Slayer, H&R Block, and Intuit were also sending specific types of data to Meta and Google.

The audit on Tax Slayer revealed that their embedded Pixel was gathering and sharing information such as phone numbers, the name of the user filling out the tax forms, and names of any dependent added to the return.

An audit on Intuit, America’s largest online filing software, revealed that the company did employ a Pixel but did not send financial information to Meta, but instead sent usernames and information about the last time a device signed into the Intuit account. Whereas the audit into H&R Block revealed that information was being gathered and shared on filers’ health savings account usage as well as dependents’ college tuition grants and expenses.

Tax filing is estimated to be an $11 billion industry in the United States with nearly 150 million individual returns filed electronically in 2021 according to this article. Free tax filing preparation and filing options do exist, but it’s limited to people making $73,000 or less and tends to be difficult to use.

Utilizing the Pixel during their tracking, The Markup found that the Internal Revenue Service directs taxpayers attempting to file for free to some of these tax filing websites with embedded Pixels. TaxAct and Tax Slayer are part of an agreement known as the Free File Alliance. TurboTax (“Intuit”) and H&R Block had participated in this program in the past. Several days after this report was published, a class action lawsuit was filed against Meta in the Northern District of California, John Doe and Jane Doe v. Meta Platforms Inc., et al., 3:22-cv-07557.

Pixel Healthcare and Patient Data

Pixels are also utilized by some healthcare systems and individual medical providers in the United States. In another lawsuit regarding Pixel litigation against Meta in the Northern District of California, Jane Doe v. Meta Platforms Inc., et al., 3:22-cv-04293-AGT, the plaintiff alleges that at least 664 hospital systems or medical provider websites have sent data to Meta via its Pixel tracking tools. The plaintiff argues that this tracking of her private health information is in violation of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (“HIPAA”)

HIPAA protects the privacy of individually identifiable health information by allowing only certain uses and disclosures of health data, such as for research purposes – but only if this data can’t be linked back to a particular patient. Currently under HIPAA, releasing data that is not properly de-identified could be considered a breach of HIPAA.

Recently on January 30, 2023, a class-action lawsuit was filed in the Tenth Judicial District of Louisiana regarding a local health care provider, Willis-Knighton Medical Center using Pixel tracking tools to send sensitive patient health data to Meta. The plaintiff in Jacqueline Horton, individually and on behalf of others similarly situated v. Willis-Knighton Medical Center, 93767-B, brought action against Willis-Knighton Medical Center for ‘exposing highly sensitive personal information to third parties without their knowledge or consent.’ The Louisiana case differs from California’s because California is one of the handful of states that has passed a statute related to video privacy and consumer protection.

In Jane Doe v. Meta Platforms Inc., the website allegedly shared information related to scheduling appointments with a doctor and reviewing test results. The California suit is seeking damages paid to consumers under the Video Privacy Protection Act (“VPPA”) 18 U.S.C. § 2710. This case was also brought under the California Confidentiality of Medical Information Act, that allows for damages of $1,000.00 per violation. In addition, the California court could potentially force hospital systems named in the suit to clearly disclose that their website uses Pixels to share data with Meta. The Plaintiff is also asking the judge to order that Meta delete sensitive health information that could be used to generate specific ads. This case will highlight misunderstandings of how HIPAA protects health information that’s in the hands of health care providers, insurers or any other entity currently subject to existing HIPAA provisions.

Origins of Pixel Litigation Lawsuits

The VPPA regulates the disclosure of information about consumers’ consumption of video content and imposes prescriptive requirements to obtain consumers’ consent to such disclosure(s). The law was originally enacted in 1988, a year after a journalist published Supreme Court Justice Robert H. Bork’s video rental history during his nominee process in 1987. The rental history contained no salacious details however and Congress quickly acted to pass the VPPA. The act reads:

The VPPA prohibits a person or business that rents, sells, or delivers prerecorded “video cassette tapes or similar audio visual materials” from “knowingly disclos[ing], to any person, personally identifiable information concerning any consumer of such provider . . . .,” absent informed, written consent as defined by the VPPA. 18 U.S.C. § 2710(a)(3). If liability is found, the VPPA allows consumers to seek the following remedies – (1) statutory damages in the amount of $2,500 per violation, (2) punitive damages, and (3) recovery of attorneys’ fees. 18 U.S.C. § 2710(c).

The VPPA was originally enacted to address the concept of a video tape service provider (“VTSP”). This was associated with traditional video rental stories and was rarely invoked as of lately. As online video services became more prevalent, the VPPA began to create legal barriers to major businesses and marketing opportunities for them. Prior to Congress amending the VPPA in 2013, the law created a strange legal paradigm: An organization’s business model involving the provisions to consumers, either on a standalone basis or as part of its broader online platform of online video content (such as a social media company), makes the organization qualify as a VTSP.

Congress amended the VPPA in 2013 to provide that disclosure of consumer data to third parties is not wrongful if the consumer elects to give ‘informed, written consent in a form that is distinct and separate from any form setting forth other legal or financial obligations of the consumer at the time the disclosure is sought, or in advance for set period of up to two years.

Under the amendment, the VPPA does provide a number exceptions that permit information being disclosed to third parties. Remarkably, one of those exceptions allows the sharing of information about the user ‘to any person if the disclosure is solely of the names and addresses of consumers and if: (i) the VTSP has provided the consumer with the opportunity, in a clear and conspicuous manner, to prohibit such disclosure; and (ii) the disclosure does not identify the title, description, or subject matter of any videos or other audio-visual material; however, the subject matter of such materials may be disclosed if the disclosure is for the exclusive use of marketing goods and services directly to the consumer.’

These exceptions allow the VPPA to permit the disclosure of the name and address of the user together with the identify of the VTSP and subject matter of the video content so long as the intended purpose is for direct marketing. The VPPA has since been challenged in several distinguishable cases decided in 2015 primarily on the grounds of violation of privacy.

Recent Developments in Pixel Litigation

The VPPA has come under consumer and legal scrutiny in recent years. Several important legal rulings have largely curtailed individual and collective efforts to declare violations under the VPPA. In Ellis v. Cartoon Network Inc., 803 F.3d 1251 (11th Cir. 2015), it was opinioned that, Consumers who use free mobile applications do not quality as ‘subscribers’ under the VPPA. The Ninth Circuit Court also opinioned two cases in 2015 regarding exceptions to the VPPA.

In Rodriguez v. Sony Computer Entm’t Am., LLC, 801 F.3d 1049 (9th Cir. 2015), an intra-corporate disclosure of personal information does not violate the VPPA. Then it was also decided by the 9th Circuit Court in another 2015 opinion Mollett v. Netflix Inc. 795 F.3d 1062 (9th Cir. 2015) that VTSPs cannot be held liable under the VPPA for circumstances where subscribers’ personal information was displayed on devices, such as televisions, that could potentially be viewed by third parties. This Court said that ‘viewing of such devices was beyond the companies’ control.’

These recent rulings narrowed the scope of the VPPA and helped provide definitions for the outdated video-store era law. Civil lawsuits across the nation related to Pixel litigation continues to barrage the integrity of the VPPA.

IHEARTMEDIA, Inc. is facing a lawsuit for allegations of violations of the VPPA in the Middle District of Florida Gloria Talley, individually and on behalf of herself and all others similarly situated v. IHEARTMEDIA, Inc., 8:32-cv-00215. Similarly the popular chicken chain, Chick-Fil-A is facing a similar class action lawsuit in the Northern District of California in Keith Carroll, individually and on behalf of all others similarly situated v. Chick-Fil-A, Inc., 3:23-cv-00314.

As lawsuits continue to mount against Meta and Google, the integrity of the VPPA is thrown into question. It is likely that one of the pending actions across the nation will eventually land the law itself into further judicial review, or if Congress acts, could create an entirely new blanket law altogether to help address the rapid interference and sharing of consumer data.